Sustaining Knowledge of Forest Ecosystems

“Effective management of ecosystems is constrained both by the lack of knowledge and information about different aspects of ecosystems and by the failure to use adequately the information that does exist in support of management decisions.”

(Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, Summary for Decision-makers – MA 2005, p. 23)

The stability of global ecosystems depends crucially on the health and stability of forests and forest soils. Forests safeguard the terrestrial system’s biodiversity and regulate both the climate and natural processes within mountain watersheds, i.e. by mitigating soil erosion and floods.

Soils build up the rich foundation of forests, where the microscopic life of bacteria, as well as insects and fungi create a regenerative self-sustaining system, physically bounded, but of infinite complexity, whose connections are mostly unknown.

Indeed, the regenerative processes of forests but, more generally, of the biosphere are only superficially understood since their deep functioning is far from being fully perceived and analysed.

And yet we humans have developed a self-understanding, a way of thinking and living ever more divorced from natural processes, entrenched in a path-dependent pattern of human behaviour, only suitable for a time when we weren’t yet able to alter Earth’s geosystems.

And so, we are used to intervening and modifying geosystems profoundly without worrying about the possible wider outcomes of our actions, simply because we seldom admit a lack of balance between our power to alter natural processes and our knowledge of those same processes.

Too few know that the thin layer that lies below our feet holds our future. Soil and the multitude of organisms that live in it provide us with food, biomass and fibres, raw materials, regulate the water, carbon and nutrient cycles and make life on land possible. It takes thousands of years to produce a few centimetres of this magic carpet.

Soil hosts more than 25% of all biodiversity on the planet1 and is the foundation of the food chains nourishing humanity and above ground biodiversity. This fragile layer will be expected to feed and filter drinking water fit for consumption to a global population of nearly 10 billion people by 2050.

Healthy soils are also the largest terrestrial carbon pool on the planet. This feature, coupled with their sponge-like function to absorb water and reduce the risk of flooding and drought, makes soil an indispensable ally for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

(European Commission, EU Soil Strategy for 2030, par. 1)

The state of Nature and of forests reveal an urgent need for transformative change in our ways of life, to escape the path-dependent pattern which assumes an unbounded system of infinite resources

Forests, forest soil and their ecosystem services deserve particular attention as they are essential for preserving both overall ecosystem functionality and its capacity to regulate climate and safeguard biodiversity.

They display a broad range of functions and services, depending on regional and local climate, demography, social and economic conditions, such as the production of wood and food and the provision of energy and recreational activities.

The state of forests shows the need for transformative change:

- the average condition of forests is under increasing strain from natural processes as well as from increased human activity and pressures;

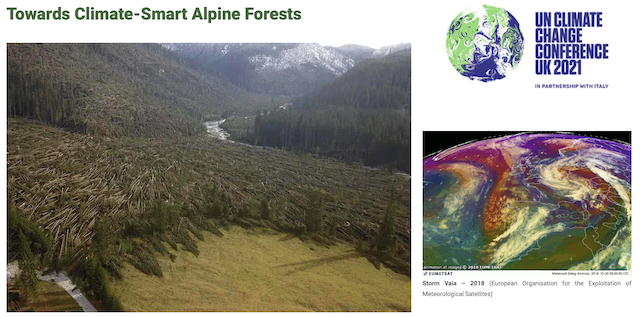

- biotic and abiotic forest damage can have devastating effects on forest ecosystems locally. Large-scale forest disturbances have become increasingly frequent, such as severe storms, extreme droughts and heat waves, and large-scale pest outbreaks;

Forests, as a core part of Nature, are in a state of crisis. The five main direct drivers of biodiversity loss – changes in land and sea use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species (IPBES, The global assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem services. Summary for policy makers, B) – are forcing Nature into rapid retreat with almost three quarters of the Earth now altered.

As a consequence, global wildlife populations have fallen by 60% as a result of human activities in the last four decades with more species under risk of extinction than at any other time in human history.

“European forests are under increasing strain – partly as a result of natural processes but also because of increased human activity and pressures. […] Climate change continues to negatively affect European forests, particularly but not only in areas with mono-specific and even-aged forest stands. Climate change has also brought to light previously hidden vulnerabilities aggravating other destructive pressures such as pests, pollution and diseases, and it affects forest fire regimes, leading to conditions under which the extent and intensity of forest fires in the EU will increase in the next years. Tree cover loss has accelerated in the last decade, because of extreme weather events and increase in harvesting for different economic purposes.”

(EU Commission, New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, par. 1)

“Biotic and abiotic forest damage can have a devastating effect on forest ecosystems locally. […] a growing frequency of large-scale forest disturbances has been observed recently, including extreme droughts, heat waves, extensive bark beetle outbreaks, and more extensive forest fires.

Deposition of air pollution has continuously decreased over the last 25 years; however, some pollutants still locally exceed critical loads.

On average, the condition of European forests is deteriorating. Mean foliage loss of trees increased at 19% of monitoring plots, more than double the number of plots where foliage improved in the period 2010-2018.”

(Forest Europe, State of Europe’s Forests 2020, Summary for Policy Makers)

“Forest, forest soil and ecosystem services deserve specific attention. According to FRA- 2015 (FAO, 2016), forests represent the second largest type of use of land: 3.999 M ha or 30.6% of land (excluding Antarctica and Greenland). Forests differ greatly around the world and have a broad range of functions at the global and local scale, depending on climate, demography, social and economic contexts (HLPE, 2017).

Forests display a broad range of interconnected functions and services contributing to the production of wood and food, the provision of energy and recreational activities, the preservation of biodiversity and fundamental ecosystem functions.”

(European Commission, Mission Area: Soil Health and Food. – Foresight on Demand Brief in Support of the Horizon Europe Mission Board, August 2022, Executive Summary and Introduction)

The climate and biodiversity crises are directly connected, “but just as the crises are linked, so are the solutions”

The climate and biodiversity crises are directly connected. The state of forests shows how climate change accelerates and aggravates pressures on Nature while, in turn, climate change itself is impacted by the loss and impaired health of forests.

“But just as the crises are linked, so are the solutions” (EU Commission, New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, par. 1). Despite all our scientific efforts, we may never close the gap between our power to alter natural processes and truly deep knowledge of these processes. The only rational answer to the deterioration of natural ecosystems is to make a transformative change in our way of thinking and living, escaping the path-dependent pattern which assumes an unbounded system of unlimited resources.

“Despite this urgent moral, economic and environmental imperative, nature is in a state of crisis. The five main direct drivers of biodiversity loss – changes in land and sea use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species – are making nature disappear quickly. We see the changes in our everyday lives: concrete blocks rising up on green spaces, wilderness disappearing in front of our eyes, and more species being put at risk of extinction than at any point in human history. In the last four decades, global wildlife populations fell by 60% as a result of human activities. And almost three quarters of the Earth’s surface have been altered, squeezing nature into an ever- smaller corner of the planet.

The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis are intrinsically linked. Climate change accelerates the destruction of the natural world through droughts, flooding and wildfires, while the loss and unsustainable use of nature are in turn key drivers of climate change. But just as the crises are linked, so are the solutions.”

(European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, par. 1)

Protection, restoration and sustainable multifunctional management are the cornerstones of a transformed human approach to nature and forests

The state of forests shows how the climate and biodiversity crises are directly connected to each other, and how Nature is a vital ally in the fight against climate change.

Therefore, the need for a transformative change involves nature-based solutions across three different approaches to Nature that strengthen the resilience of forests and their capacity for climate adaptation: protection, restoration and sustainable multifunctional management.

Globally and also in the EU there are legal frameworks, strategies and action plans to protect nature and restore habitats and species. But, generally, protection has been incomplete, restoration has been small-scale, and their implementation and enforcement have been limited.

“The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis are intrinsically linked. […] But just as the crises are linked, so are the solutions. Nature is a vital ally in the fight against climate change. Nature regulates the climate, and nature-based solutions, such as protecting and restoring wetlands, peatlands and coastal ecosystems, or sustainably managing marine areas, forests, grasslands and agricultural soils, will be essential for emission reduction and climate adaptation.”

(European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, par. 1)

“The onset of climate change means forest change […] very few forests will either not be strongly affected by climate change, or will not require immediate management action to reduce their vulnerability to climate change.”

(EU Commission, New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, par. 3)

“The EU has legal frameworks, strategies and action plans to protect nature and restore habitats and species. But protection has been incomplete, restoration has been small- scale, and the implementation and enforcement of legislation has been insufficient.

To put biodiversity on the path to recovery by 2030, we need to step up the protection and restoration of nature. This should be done by improving and widening our network of protected areas and by developing an ambitious EU Nature Restoration Plan.”

(European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, par. 2)

Governance of an anthropised planet - Protection

Expanding and effectively looking after protected areas, including freshwater, matters greatly for defending biodiversity, above all against the background of climate change

This involves designing ecologically meaningful networks of interlinked protected areas to cover crucial biodiversity areas, while also taking into account society’s many different views on the value of Nature.

Effective preservation of protected areas requires a comprehensive approach including a) monitoring and implementation systems, b) extended care of valuable unprotected areas, and c) addressing the pressure of competing interest groups.

Successful protection involves stakeholder cooperation and the direct engagement of local people by using instruments such as collaborative scenarios and spatial and cross-border conservation planning.

“Expanding and effectively managing the current network of protected areas, including terrestrial, freshwater and marine areas, is important for safeguarding biodiversity (well established), particularly in the context of climate change. Conservation outcomes also depend on adaptive governance, strong societal engagement, effective and equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms, sustained funding, and monitoring and enforcement of rules (well established). National Governments play a central role in supporting primary research, effective conservation and the sustainable use of multi-functional landscapes […]. This entails planning ecologically representative networks of interconnected protected areas to cover key biodiversity areas and managing trade-offs between societal objectives that represent diverse worldviews and multiple values of nature (established but incomplete). Safeguarding protected areas into the future also entails enhancing monitoring and enforcement systems, managing biodiversity-rich land […] beyond protected areas, addressing property rights conflicts and protecting environmental legal frameworks against the pressure of powerful interest groups. In many areas, conservation depends on building capacity and enhancing stakeholder collaboration, involving […] local communities to […] proactively using instruments such as landscape-scale […] participatory scenarios and spatial planning, including transboundary conservation planning (well established).”

(IPBES, The global assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem services. Summary for policy makers, n. 34)

“Evidence shows that the targets defined under the Convention on Biological Diversity are insufficient to adequately protect and restore nature. Global efforts are needed and the EU itself needs to do more and better for nature and build a truly coherent Trans-European Nature Network.

[…] In this spirit, at least 30% of the land and 30% of the sea should be protected in the EU. […]

Within this, there should be specific focus on areas of very high biodiversity value or potential. These are the most vulnerable to climate change and should be granted special care in the form of strict protection. Today, only 3% of land and less than 1% of marine areas are strictly protected in the EU. We need to do better to protect these areas. In this spirit, at least one third of protected areas – representing 10% of EU land and 10% of EU sea – should be strictly protected. This is also in line with the proposed global ambition.

As part of this focus on strict protection, it will be crucial to define, map, monitor and strictly protect all the EU’s remaining primary and old-growth forests. […]

[…] Member States will be responsible for designating the additional protected and strictly protected areas. Designations should either help to complete the Natura 2000 network or be under national protection schemes. All protected areas will need to have clearly defined conservation objectives and measures. […]”

(European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, par. 2.1.)

Governance of an anthropised planet – Restoration

Scientific findings generally show that biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystems are advancing at an alarming rate.

This evidence is forcing policymakers and legislators to act fast to restore forests as well as freshwaters, wetlands and agricultural land.

As part of the implementation of the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, the Commission will propose a legally binding instrument for the restoration of ecosystems, prioritising those with the most potential to capture and store carbon and to prevent and limit the impact of natural disasters.

Within this perspective, “ecosystem restoration” has been defined as the process of actively or passively assisting the recovery of an ecosystem towards or to good condition as a means of conserving or enhancing biodiversity and ecosystem resilience (see Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, of 22.6.2022, Article 3)

Given the threats posed to forests and to their global relevance, policymakers worldwide also focus on the restoration of forest ecosystems. Authorities and stakeholders are required to put in place restoration measures needed a) to enhance biodiversity of forest ecosystems and b) to pursue specific targets based on updated scientific evidence, such as the level of the following indicators: standing deadwood, lying deadwood, share of forests with uneven-aged structure; forest connectivity, common forest bird index and the stock of organic carbon (see Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, of 22.6.2022, Article 10 – Restoration of forest ecosystems).

“This [IPCC] report recognizes the interdependence of climate, ecosystems and biodiversity, and human societies and integrates knowledge more strongly across the natural, ecological, social and economic sciences than earlier IPCC assessments. The assessment of climate change impacts and risks as well as adaptation is set against concurrently unfolding non-climatic global trends e.g., biodiversity loss, overall unsustainable consumption of natural resources, land and ecosystem degradation, rapid urbanisation, human demographic shifts, social and economic inequalities and a pandemic.”

(IPCC, Working Group II contribution to Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2022. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. SPM.A: Introduction)

“The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 […] underlined that protection alone would not be enough: to reverse biodiversity loss, greater efforts are needed to bring nature back to good health across the EU, in protected areas and beyond. Therefore, the Commission committed to propose legally binding targets to restore degraded EU ecosystems, in particular those with the most potential to remove and store carbon and to prevent and reduce the impact of natural disasters.”

(European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, 22.06.2022, Explanatory Memorandum, Context of the Proposal)

“The evaluation of the biodiversity strategy up to 2020 identified voluntary rather than legally binding targets as a reason why ecosystem restoration has failed. The subsequent lack of commitment and political priority are major barriers to allocating funding and resources to restoration work.

In addition, the Birds and Habitats Directives do not set deadlines for maintaining or restoring natural habitats and species to favourable conservation status. The Directives also lack specific requirements to restore ecosystems that lie outside the Natura 2000 network. To address these shortcomings, this proposal makes restoring certain species and habitats mandatory, inside and outside the Natura 2000 network, and with clear deadlines.”

(European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, 22.06.2022, Explanatory Memorandum, 3. Results of Ex-post Evaluations […])

Governance of an anthropised planet – Sustainable multifunctional management

There are significant opportunities for forest management practices which address simultaneously the multiple functions and ecosystem services of forests, such as safeguarding biodiversity, improving climate resilience and carbon-sink functionalities, delivering timber production and maintaining rural livelihoods.

These practices aim at a multifunctional use of forests and at the integration of conservation measures with wood production, based on an overarching Sustainable Forest Management approach.

Sustainable Forest Management means the stewardship and use of forest lands in a way, and at a rate, that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, regeneration capacity, vitality and their potential to fulfil, now and in the future, relevant ecological, economic and social functions, at local, national and global levels, and that does not cause damage to other ecosystems (Forest Europe, State of Europe’s forests 2020).

This wide range of nature-near practices is being continuously updated as new scientific evidence emerges. Against this background, the New EU Forest Strategy 2030 has envisaged moving towards a definition of principles and guidelines and to a voluntary certification scheme, called “Closer-to-Nature Forest Management”.

In this perspective, Closer-to-Nature Forest Management has been defined as an overarching “umbrella” covering all approaches and terminologies, which, under the auspices of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), support biodiversity, resilience and climate adaptation in managed forests and forested landscapes (European Forest Institute, Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. From Science to Policy 12, Introduction, 2022). The underlying principles are:

- Retention of habitat trees, special habitats, and dead wood

- Promoting native tree species as well as site adapted non-native species

- Promoting natural tree regeneration

- Partial harvests and promotion of stand structural heterogeneity

- Promoting tree species mixtures and genetic diversity

- Avoidance of intensive management operations

- Supporting landscape heterogeneity and functioning

“Currently, there is a transition in many European regions towards a more multifunctional forest management approach. The overall objective is to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services to benefit present and future generations and societies, while enhancing biodiversity protection and reversing the degradation of ecosystems. Inevitably, seeking to provide this diversity of services can result in a decline in the supply of individual elements of the portfolio (van der Plas et al. 2016).

In general terms, natural forest ecosystems have been robust as a consequence of long-term adaptation to regional and local conditions. Their apparent resistance and resilience – i.e. their ability to withstand stress and recover from disturbances – is mainly based on structural, functional and genetic diversity.

However, a widespread focus on wood production in previous centuries has resulted in a simplification and homogenization of European forests in many regions, often exemplified by the creation of even-aged and single species stands. This has weakened the natural robustness of the forests, which is further chal- lenged by global change (climate change, nutrient enrichment and introduction of new biotic stressors). These developments are already affecting forests in the form of increasingly severe disturbances (extreme heat and droughts, storms, fires, bark beetles, native and imported pests and pathogens), that compromise their capacity to sustain multiple ecosystem services.

[…] To give back space to nature, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 has proposed an overall target to protect at least 30% of the EU land area under an effective management regime, of which one-third (i.e. 10% of the EU land area) should be put under strict legal protection. This is consistent with the ‘third of third’ principle in conservation science (Hanski 2011). Forest ecosystems will need to contribute to this goal. Besides their contribution to the strict protection target, the integration of conservation measures into the management of multifunctional (production) forests is of crucial importance.”

(European Forest Institute, Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. From Science to Policy 12, Introduction, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36333/fs12)

“Closer-to-Nature Forest Management is a new concept proposed in the EU Forest Strategy for 2030. The idea is to provide a vision of and direction for managed forests in Europe, which improves their conservation values as well as their climate resilience […]

Efforts to conserve forest biodiversity rely on two overlapping approaches: 1) setting aside forests specifically for nature conservation in areas excluded from wood production (functional segregation) and 2) incorporating conservation measures within production-oriented forests (functional integration). These two approaches support each other […]

Europe’s forests and woodlands are diverse. With a history of over 6,000 years of intensive interaction between man and nature, European landscapes and forests support important social, economic and biological values (Nocentini and Coll 2013). […] Strategies and benchmarks for biodiversity conservation thus include both naturalness and traditional cultural woodlands managed by small-scale or peasant farmers, traditional livestock keepers/pastoralists (Knight 2016; Angelstam et al. 2021). Similarly, a wide range of approaches for integrating conservation measures in forests managed partially or primarily for wood production has been developed. These include Close-to-Nature Forestry, Continuous Cover Forestry, Retention Forestry, Mimicking Natural Disturbance, Emulating Natural Processes, Ecosystem Management, Ecological Forestry. They are in- spired by the structures and successional trajectories observed in natural forests in their respective region […]

In addition, a wide range of nature-near approaches are under development to support forest health and not least the adaptation of forest and forest landscapes to climate change and other external (global) threats e.g. climate smart forestry […]”

(European Forest Institute, Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. From Science to Policy 12, Introduction, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36333/fs12)

“Forest management practices that preserve and restore biodiversity lead to more resilient forests that can deliver on their socio-economic and environmental functions. Therefore all forests should be increasingly managed so that they are sufficiently biodiverse, taking into account the differences in natural conditions, biogeographic regions and forest typology. There are significant opportunities for win-win measures, which simultaneously improve forest productivity, timber production, biodiversity, carbon sink function, healthy soil properties and climate resilience. A greater diversity of forest ecosystems and species, and the use of well- adapted genetic resources and ecosystem-based approaches to forest management can enhance long‐ term adaptability and forests’ capacity to recover and self-organise.”

(EU Commission, New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, par. 3.2)

“Taking care of forests soil is particularly important, as there is a strong interdependence between trees and the soil on which they grow. For trees to thrive, tree roots need to obtain all essential elements and nutrients from the soil. Therefore, the soil properties and soil ecosystem services must be protected as the very foundation of healthy and productive forests. As an example, undue use of unsuitable machinery that cause negative environmental impacts such as soil compaction should be avoided.”

(EU Commission, New EU Forest Strategy for 2030, par. 3.2)